In Recollections of My Nonexistence, Rebecca Solnit describes her formation as a writer and as a feminist in 1980s San Francisco, in an atmosphere of gender. Recollections of My Nonexistence is a personal, cultural, political, and journalistic hybrid narrative about formative years in the life of Rebecca Solnit. A first-person account from San Francisco in the 1980s, she describes finding her voice, and invokes the possibility of others finding their voices as well.

Itis often said of the writer Rebecca Solnit that her work “resonates.” It’s hardto find an article about her that doesn’t include that word. At a time whenfeminism is about finding others who have lived on the same frequency (#metoo,#yesallwomen), a thinker like Solnit, who gravitates toward identifying commondenominators in the female experience (mansplaining, gaslighting, silencing,etc.) is primed to resonate.

Nowhereis resonance better measured than on social media, where Solnit’s work is sharedand circulated expeditiously. On her Facebook page, which has over 150,000followers, she shares news articles, political commentary, and posts that readlike magazine essays; it has become an online community unto itself forfeminists looking for digital platforms to express rage, hope, and everythingin between. That her work feels tailor-made for the kind of collectiveexperience social media enables is no coincidence. Solnit’s rise to new levelsof fame stems from one of her essays, “MenExplain Things to Me,” going viral online. (She had in fact publishednearly a dozen books by the time that essay appeared.) The piece, writtenoriginally for the Los Angeles Times, popularized the word mansplaining, a term that accomplished the rare feat of articulating a familiar butas-yet-unrecognized experience.

Solnit’snew book,Recollections of My Nonexistence, takes us to her formative years, when she was experiencingpatterns of misogyny she could not name (and, as she explains, therefore could notfight). “I was often unaware of what and why I was resisting,” she reflects,“and so my defiance was murky, incoherent, erratic.” She came to see this condition,and that of all women, as a kind of imperative toward nonexistence. The book,a memoir and creative autobiography, is meant as an antidote, a guide toavoiding self-effacement in a world where women are routinely disappeared andquieted down. “I can wish that the young woman who came after me might skipsome of the old obstacles,” she writes, “and some of my writing has been towardthat end, at least by naming these obstacles.”

Thememoir revisits many of the concepts—mansplaining, gaslighting, streetharassment, the transformative power of women’s stories—that appear both inSolnit’s previous work and in the online feminist ecosystem that has supportedit. The result feels perhaps too familiar, a book so focused on existingconversations, so tightly structured around relatable insights, that it feels—dareI say it—designed to do little more than resonate online.

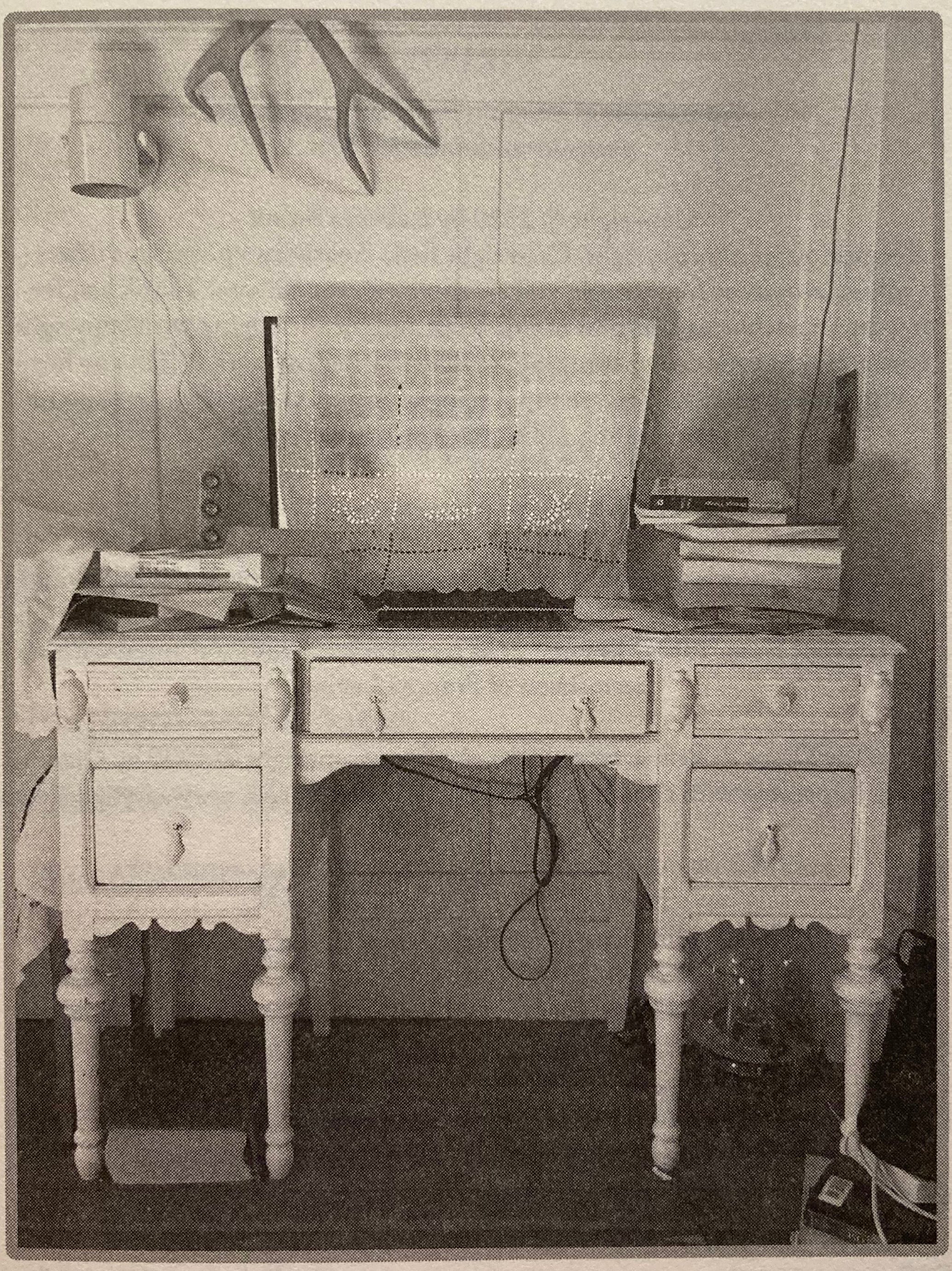

Solnit grew up in a troubled household in a suburbof San Francisco. After a brief stint in Paris as a teenager, she returned to northernCalifornia where she took the GED at 15 and graduated from San Francisco StateUniversity in 1981 at age 20. The year before, she moved into an apartment in apredominately African American neighborhood near the city’s Panhandle district. “Later on I’d come to understand gentrification and the role that I likelyplayed as a pale face making the neighborhood more palatable to other palefaces,” she writes, “but I had no sense at the start that things would changeand how that worked.” Solnit would spend the next two decades in this studioapartment, writing near her bay window on a desk gifted to her by a friend whowas nearly stabbed to death by an ex-boyfriend. “Now I wonder,” she reflects, “ifeverything I have ever written is a counterweight to that attempt to reduce ayoung woman to nothing.”

Oneof the strengths of the book is the way Solnit manages to think throughnonexistence as both a weapon and a shield. In an early chapter, she writesabout how she learned the “art of nonexistence” as a young teenager, trying toavoid the gaze of older men, including some in her own family. “At twelve andthirteen and fourteen and fifteen, I had been pursued and pressured for sex byadult men on the edge of my familial and social circles.” Throughout heradolescence and young adulthood, Solnit begins looking for ways to exist as littleas possible, from turning thin to the point of frailty to becoming constantlyaware of exits and escapes: “I became expert at fading and slipping andsneaking away, backing off, squirming out of tight situations … at graduallydisengaging, or suddenly absenting myself.” Solnit often writes about herdecision to become a writer as a desire to name the various violences thatchased her. It is also possible that the life of an author—tucked away inarchives, working quietly in writing nooks—presented a way to live a lifephysically out of view.

Nonexistencecan also be literal for Solnit, as the chapter “Annihilators” makes clear. The1970s and 1980s saw a spike in the number of serial killers, leading to ageneral sense of anxiety across the country, one most keenly felt by youngwomen who were their primary targets. “It was the era” Solnit explains “of theNight Stalker and the middle-aged white man known as the Trailside Killer (whoraped and killed women hikers on the trails I hiked on) and the Pillow-caseRapist and the Beauty Queen Killer and the Green River Killer and the Ski MaskRapist and many other men who rampaged up and down the Pacific Coast withoutnicknames.” Solnit recalls a harrowing story of walking home following a NewYear’s Party and being followed closely by a man on a dark, empty street. Whileshe ultimately finds her way out of the situation, the trauma stays with her;it is one of the most detailed and specific memories that Solnit recalls fromthis period in her life.

Solnitis especially attuned to the normalization of violence against women in popularculture and belles lettres. In this way, Recollections of My Nonexistenceis often closer to a work of cultural criticism than memoir—though in combiningthe two, it asks us to think about how much our sense of self-worth and socialvalue is shaped by the cues we get from films, books, and television. Uses for mac fix. “In thearts,” she notes, “the torture and death of a beautiful woman or a young womanor both was forever being portrayed as erotic, exciting, satisfying.” Shealludes to the work of Alfred Hitchcock, Brian De Palma, and David Lynch,directors whose signature works centered on murdered women (Psycho, Twin Peaks, etc.): “Legions of women were being killed in movies,in songs, in novels, and in the world, and each death was a little wound, alittle weight, a little message that it could have been me.” For Solnit, the aestheticizationof these stories amounts to a kind of delegitimization of the very real fearsshe harbored at the time about her safety. It “was a kind of collective gaslighting” shewrites, tantamount to “[living] in a war that no one around me wouldacknowledge as a war.”

Itis hard to disagree with anything Solnit says here, but one wonders if that isa shortcoming. Though Solnit makes references, largely in asides, to the wayswomen’s experiences are complicated by race, class, and sexual orientation,there is little real mining of these disjunctures. In Recollections of MyNonexistence, Tyke. women and minorities largely exist as innocent, interestingfigures who add “vitality” to spaces, who fit neatly into Solnit’s worldviewwherein misogyny is largely a thing that straight white men (and Kanye West)do.

When resonance is treated as anethos in and of itself, we begin to silence ourselves, and solidarity becomeslittle more than a new kind of nonexistence.Shepasses by black churches and revels in the idea that she is “never too far fromdevotion,” but does not consider the potential collision of Christian modestywith feminist ideas about sexual liberation. She writes that she likes livingin California because it “faces Asia” but does not engage with the uniquecontours of Pacific feminism. The gay men in the Castro make great friends forSolnit—“Oh, how I was free to be funny or dramatic or preposterous aroundthem,” she exclaims—but the capacity of queer men to enact misogyny is neverexplored.

A few years ago, Viviane Fairbank of The Walruswrote a piece titled“Why I Don’t Read Rebecca Solnit,” that articulated some of the same anxietiesI hold about Solnit’s relatively unquestioned status as an important voice incontemporary feminism. For Fairbank, Solnit’s writing embodies a new, watered-downethos of feminist solidarity, “call it ‘pop feminism,’—that addresses onlytopics we can safely agree on.” Fairbank traces Solnit’s belief in the power ofwomen’s stories to the consciousness-raising work of 1960s feminists, remindingus that these stories were meant to lead to “debate thattriggers policy change, social reform, or even popular demonstrations. Solnitnever makes it past anecdotal evidence.” Likewise, I kept waiting for this bookto spin out more, to think, for instance, about how nonexistence functions undercapitalism through the erasure of women’s labor, or what it means when womenbecome not invisible but indeed hypervisible as justifications for militaryintervention (i.e., the U.S. government’s insistence that its invasion would“liberate” Afghan women).

Author Rebecca Solnit

While Solnit has written extensivelyelsewhere on climate and anti-nuclear activism, those issues often recede intothe background in Recollectionsof My Nonexistence. Thereis a distinct lack of politics as policy here, perhaps because a truly feministpolitical vision might make some of Solnit’s white and upper-middle-classreaders uncomfortable. But that is what happens when resonance is treated as anethos in and of itself; we begin to silence ourselves, and solidarity becomeslittle more than a new kind of nonexistence.

Microsoft edge translate. Open a webpage in Microsoft Edge. The browser automatically detects the language of the page.

In Recollections of My Nonexistence, Rebecca Solnit describes her formation as a writer and as a feminist in 1980s San Francisco, in an atmosphere of gender violence on the street and throughout society and the exclusion of women from cultural arenas. She tells of being poor, hopeful, and adrift in the city that became her great teacher, and of the small apartment that, when she was nineteen, became the home in which she transformed herself. She explores the forces that liberated her as a person and as a writer--books themselves; the gay community that presented a new model of what else gender, family, and joy could mean; and her eventual arrival in the spacious landscapes and overlooked conflicts of the American West.

Beyond being a memoir, Solnit's book is also a passionate argument: that women are not just impacted by personal experience, but by membership in a society where violence against women pervades. Looking back, she describes how she came to recognize that her own experiences of harassment and menace were inseparable from the systemic problem of who has a voice, or rather who is heard and respected and who is silenced--and how she was galvanized to use her own voice for change.

“Much more than a feminist manifesto . . . Solnit movingly describes her efforts to fashion ‘the self who will speak’ . . . There are phrases, such as ‘women’s stories,’ ‘silencing,’ or ‘gaslighting,’ that contemporary discourse has emptied out. Solnit revives these terms with the breath of their own histories.” —Katy Waldman, The New Yorker

'At the same time that [Solnit] describes her forays into her past, she invites us to connect pieces of her story to our own, as a measure of how far we've come and how far we have left to go.' —Jenny Odell, The New York Times Book Review

“Throughout her rich body of work, essayist and critic Rebecca Solnit has revealed pieces of herself in writings about the beauty of getting lost, the joys of walking both for pleasure and with purpose, and perhaps most famously, the indignity of being mansplained to. At last, she uses her eagle eye to explore her own life. Recollections of My Nonexistence is a marvel: a memoir that details her awakening as a feminist, an environmentalist, and a citizen of the world. Every single sentence is exquisite.” —Maris Kreizman, Vulture

“[A] splendid memoir of longings and determinations, of resistances and revolutions, personal and political, illuminating the kiln in which one of the boldest, most original minds of our time was annealed.” —Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

“A clarion call of a memoir, chronicling, in unfettered, poetic prose, her coming-of-age . . . and her emergence as one of our most potent cultural critics.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“A resonant and moving portrait of how challenging life can be in the female body.” —Time, “100 Must-Read Books of 2020”

“A deeply intimate and deeply internal book about how Solnit became one of the defining feminist thinkers of the twenty-first century [and] a nostalgic love letter to the San Francisco of her youth . . . Solnit writes beautifully and with much compassionate nuance about how the threat of violence and not just its execution colors all parts of a woman’s life, and how actual physical violence is just one of myriad ways that women are controlled, subjugated and silenced . . . This [book] is electrifying in its precision of thought and language.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Solnit has valiantly been making the case that misogynist speech and violence are on a spectrum for decades, long before mainstream acceptance of the idea . . . In Recollections of My Nonexistence, Solnit implies that just as the illness can be both dramatic and also cumulative, gradual, and imperceptible, so might be the cure. And things that feel insufficient — writing, talking, walking, teaching — do in fact represent tiny counterweights, which together shift the course of culture.” —NPR.org

“For Solnit fans, her new memoir is a glimpse of all that was ‘taking form out of sight,’ providing a key to understanding much of her work to date. Yet simply as a coming-of-age narrative, it also has much to offer someone new to her writing. [Recollections] often reverses the figure-ground relationship, portraying the emergence of a writer and her voice from a particular cultural moment and set of fortuitous influences . . . [It] often reads as a letter to young activists and women writers—less ‘back in my day’ and more ‘I fought, and am fighting, the same battles you are.’” —Jenny Odell, The New York Times Book Review

“Solnit begins this book of personal and cultural explorations with the memory of looking in a mirror and seeing herself disappear. It’s a fitting metaphor for a narrative that is as much a social history as it is a memoir, engaging questions of invisibility and silence and the way patriarchal forces seek to render women small.” —Los Angeles Times

“Solnit emphasizes the need to find poetry in survival . . . [Recollections of My Nonexistence is] a voice raised in hope against gender violence. It’s a call we should listen to.” —The Washington Post

“It is a rare writer who has both the intellectual heft and the authority of frontline experience to tackle the most urgent issues of our time. One of the reasons [Solnit] has won so many admirers is the sense that she is driven not by anger but by compassion and the desire to offer encouragement . . . That voice of hope is more essential now than ever, and this memoir is a valuable glimpse into the grit and courage that enabled her to keep telling sidelined stories.” —The Guardian (London)

“A brilliant memoir that is at once both of the moment and timeless . . . Recollections of My Nonexistence is all about liberation. And it invites us to think more broadly about what is possible in challenging times.” —John Nichols, The Progressive

“[A] feat of exacting labor, with places from decades ago remembered in their tiny details alongside a constant, simmering anger at how those same places were ordinary war zones for women.” —Vanity Fair

“A work of feminist solidarity, in which [Solnit] chooses to write not from herself alone, but ‘for and about and often with the voices of other women talking about survival’ . . . What Solnit wants most is to talk about the obstacles her younger self found . . . She’s concerned with the way women disappear, or are encouraged to abdicate their bodies and their vocation . . . [A] meditation on creativity, home, and an elusive self.” —4Columns

“[A] splendid memoir of longings and determinations, of resistances and revolutions, personal and political, illuminating the kiln in which one of the boldest, most original minds of our time was annealed.” —Maria Popova, BrainPickings

“One of the more beautiful narratives I’ve read.” —Ezra Klein, Vox

“Rebecca Solnit’s opposition to injustice in its many forms, and her relentless inquiry as a writer and reporter into a great range of issues—racial injustice, nuclear weapons, indigenous rights, male hegemony—have defined the outrage and politics of much of her generation. In Recollections of My Nonexistence she draws all these potent metaphors for inequity together into a moral stance that transcends the particulars of all her topics. This is a remarkable book—smart, brave, edgy, insightful, and authentic.” —Barry Lopez

“One of our foremost thinkers on womanhood explores the journey of her becoming in this deeply personal memoir about her youth in San Francisco. In her searing, sensitive voice, Solnit recalls the epidemic of violence against women . . . tracing her journey as a writer through her journey to speak out on behalf of women.” —Esquire

“Activist and essayist Rebecca Solnit has long captured the discomforts and difficulties of modern womanhood . . . [I]n describing [her youth], she details how she found her voice as an advocate for herself and those around her.” —Time

“Fantastic . . . Solnit generously offers the story of finding her voice – exemplary as it is – as just one of the tales 'waiting to be told' in feminism’s twenty-first century.” —BUST

“This powerful memoir reveals how Solnit’s coming-of-age as a journalist and a woman in 1980s San Francisco shaped her as a writer and a feminist. She grapples with sexual harassment, poverty, trauma, and women’s exclusion from the cultural conversation, while discovering punk rock and the LGBTQ+ community as safe havens. Her words have long empowered people who feel voiceless, and her latest book is no exception.” —Good Housekeeping

“[Solnit] couches her own lived experience . . . within a larger exploration of contemporary womanhood and an unapologetically feminist, queer lens. While beautifully exercising her own literary voice, Solnit simultaneously poses the question: Who do we allow to characterize the female experience? And what needs to happen in order for that to change?” —Parade

“An inquisitive, perceptive, and original thinker and enthralling writer . . . Solnit has created an unconventional and galvanizing memoir-in-essays that shares key, often terrifying, formative moments in her valiant writing life . . . [and] illuminates with piercing lyricism the body-and-soul dangers women face in our complexly, violently misogynist world . . . [A]n incandescent addition to the literature of dissent and creativity.” —Booklist (starred)

“While misogyny and its effect on women’s psyches is familiar territory for Solnit, as in her breakthrough 2014 essay collection, Men Explain Things To Me, here the prolific writer gets more personal than ever as she reflects upon her youth in 1980s San Francisco.” —AV Club

“Absorbing . . . A perceptive, radiant portrait of a writer of indelible consequence.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“An engaging look at Solnit’s life, which succeeds in giving voice to inequity caused by patriarchy . . . Her recollection of her feelings regarding violence and being silenced are particularly resonant . . . She knows who she is and which forces have shaped her . . . [and] realizes the power of naming inequity, violence, and oppression against women.” —Library Journal

“Enlightening . . . a thinking person’s book about writing, female identity, and freedom by a powerful and motivating voice for change.” —Publishers Weekly

Is Rebecca Solnit Married